sarahsar

Goodreads refugee (http://www.goodreads.com/user/show/1257768-sarah) exploring BookLikes.

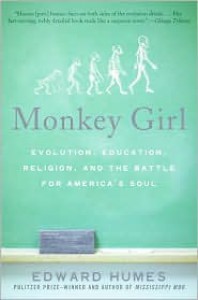

Review of Monkey Girl

The argument between creationists and evolutionists was in the news recently after the debate between Bill Nye “The Science Guy” and Ken Ham, the Australian who runs the Creation Museum. The dispute is nothing new, though. Creationists and evolutionists have been butting heads since Darwin’s day. Ken Ham’s organization Answers in Genesis represents the more extreme end of the spectrum, the “young earth” creationists who believe that the earth is only 6,000 years old and that dinosaurs and people lived at the same time.

Dinosaur and human living in harmony at the Creation Museum.

This argument grows particularly heated when it involves the public school system. Since the Scopes Monkey Trial in 1925, school boards across the country have debated first whether or not they should allow the teaching of evolution, and more recently whether or not they should allow the teaching of creationism and/or intelligent design. A recent story in Slatereported that thousands of schools are allowed to teach creationism in science classes, in spite of Supreme Court decisions like Edwards v. Aguillard in 1987 that ruled that creationism could not be taught if it was advancing a particular religion.

There may be reasons you never learned this in school (Creation Museum).

In Monkey Girl, Edward Humes recounts the 2005 court battleover teaching intelligent design in the Dover Area School District in Dover, Pennsylvania. Two young earth creationists on the school board led the push to add intelligent design to the science curriculum. Intelligent design (ID) argues that certain biological features (like bacterial flagella and the coagulation cascade) are too complex to be explained by evolution alone, and must have required a “designer.” Mainstream science finds nothing “scientific” about this concept, viewing it as a Trojan horse to get re-branded creationism into schools, but the defendants in the case insisted that the goal of including ID in the science curriculum was to improve science education and had nothing to do with religion.

Previous actions by board members made this a difficult argument to defend. When discussing including ID in science classes, one member said, “Two thousand years ago, someone died on a cross. Can we have the courage to stand up for him?” (Prologue, Monkey Girl). With statements like those, it was hard to argue that religious belief was not involved.

Humes does a good job of summarizing the case, with a helpful discussion of the historical background. Unfortunately he gets bogged down in details in telling Dover’s story. It’s as if he wants to give a narrative with the dramatic impact of William Jennings Bryan and Clarence Darrow facing off in the Scopes Trial, but the personalities here don’t have that larger-than-life flair. They are, for the most part, ordinary people with unwavering world views. That setting has a certain innate drama, but it doesn’t warrant the minute-by-minute treatment Humes gives it.

There is also an odd shift in tone throughout the book. Humes starts with a highly journalistic approach, presenting the facts and people on both sides in as fair a manner as possible. As the story progresses, though, it’s as if he loses patience, getting increasingly snarky. His Epilogue rambles strangely about right-wing pundit Ann Coulter. While there is no doubt that she is a good example of an anti-science demagogue, the rant is a bit off-topic for the book.

Monkey Girl is a good treatment of an important and still relevant topic, the inclusion of religion in science education in the public schools. It would have been a better book, though, without the excessive detail and the pretense of courtroom drama.

Better days in the Garden of Eden at the Creation Museum.

2

2