50

Followers

44

Following

sarahsar

Goodreads refugee (http://www.goodreads.com/user/show/1257768-sarah) exploring BookLikes.

I think the jury is still out as to whether or not James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake is readable at all, but Roland McHugh tackled it head-on, devoting years of his life to studying it with zealous devotion. The entomologist turned Wake expert admits, “My technique was slightly fanatical. I was so anxious to capture the undistorted experience than on reading page 29, where the first chapter ends, I tied a thread round all the remaining pages to prevent my accidentally looking ahead.” To anyone who has skimmed a page or two of Finnegans Wake, it’s hard to imagine that looking ahead could create any real spoiler problems, but McHugh was a purist.

I think the jury is still out as to whether or not James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake is readable at all, but Roland McHugh tackled it head-on, devoting years of his life to studying it with zealous devotion. The entomologist turned Wake expert admits, “My technique was slightly fanatical. I was so anxious to capture the undistorted experience than on reading page 29, where the first chapter ends, I tied a thread round all the remaining pages to prevent my accidentally looking ahead.” To anyone who has skimmed a page or two of Finnegans Wake, it’s hard to imagine that looking ahead could create any real spoiler problems, but McHugh was a purist.And that was just the first reading. McHugh went on to read, dissect, and scrutinize Finnegans Wake with complete thoroughness, telling us, “I began to annotate my copy of FW. I transferred information to it in very small writing, using a mapping pen. I could actually get two lines of writing between every two FW lines, and I used twelve different colours of ink to specify different languages.”

Soon Joyce’s inscrutable novel began to influence McHugh’s non-literary profession, when McHugh, “having left Imperial College far too obsessed with FW to think seriously about a career,” takes a job studying grasshopper acoustics in Paris, thinking that improving his French will help him with his Wake studies. He later tells us, “I was becoming increasingly convinced that to achieve a really total appreciation of the FW text I needed to move permanently to Ireland.” He did indeed make that move. I’m not sure whether or not he gave up bugs altogether, but he did eventually become a noted Joyce scholar.

As literary criticism goes, The Finnegans Wake Experience is quite entertaining, though it does raise concerns for the author’s sanity. That’s probably appropriate, though, considering that Finnegans Wake called into question Joyce’s mental health as well. From the standpoint of encouraging slightly less, shall we say, enthusiastic Joyce fans to tackle the Wake, however, The Finnegans Wake Experience is a bit demoralizing.

I kept thinking about this quote from the movie Quiz Show when I heard about Fifty Shades of Grey:

I kept thinking about this quote from the movie Quiz Show when I heard about Fifty Shades of Grey:“Cheating on a quiz show? It’s like plagiarizing a comic strip.”

I suspect Mark Van Doren wouldn’t have been too worked up over the sketchy provenance of Fifty Shades either, this Twilight fanfic inexplicably turned best-seller and cultural phenomenon.

This book has become hard to avoid. It’s front and center in bookstores, has prompted articles in the New York Times and a provocative Newsweek cover, brought in a seven-figure movie deal, and has inspired Saturday Night Live skits. Perhaps most unforgivably, it seems to have spawned the use of the phrase “mommy porn.”

So I added my name to the waiting list of more than 100 people for my public library’s electronic edition (this is a huge number of people for a digital book at my library, especially considering that they have twenty-three copies. I think Twilight itself rarely had more than ten waiting, for far fewer copies). Finally, my turn came, and . . .

There’s just not that much to say. I don’t generally read romance novels or erotica, and I haven’t read Twilight, so I don’t have much to compare this to. I have, however, read plenty of so-called “chick lit,” and I would describe Fifty Shades as a worse-than-average chick lit story with (much) more graphic sex. As far as the much-touted BDSM element goes, I counted four such scenes out of an uncountable number of descriptions of “vanilla sex” (as the characters describe it).

The writing is pretty awful, with Anastasia’s “inner goddess,” “subconscious,” and even “medulla oblongata” making appearances on almost every page, apparently as a way for her to give a third-person narrative opinion of her first-person narration of events. It’s contrived and irritating, and any decent editor would have limited E.L. James to no more than one such mention of each of Anastasia’s multiple personalities. There are numerous annoyingly unrealistic details - Anastasia is in college but needs her best friend to teach her how to shave her legs, the 2011 MacBook Christian gives her has 32 GB of RAM - but honestly, I’ve read worse.

My main impression of Fifty Shades is that it just doesn’t live up to the hype, positive or negative. Sure, some libraries have banned it, but even Stephenie Meyer doesn’t seem too upset about her storylines being ripped off, and if she’s not worried about it, I’m certainly not going to be. All of Anastasia and Christian’s antics are brazenly, well, consensual, almost to the point of being ludicrous, with a legal contract up for discussion throughout the book. Christian talks a big game about the extreme things he wants to do, but most of it never happens. And I wouldn’t be surprised if a condom company pays for product placement in the movie, because the characters keep reminding us of the importance of safe sex. Like Christian Grey himself, Fifty Shades’ bark is worse than its bite.

Rating: Probably 1 1/2 stars. It's hard to work up enough enthusiasm about this book to really hate it.

It’s hard to resist the idea of a guide to Ulysses endorsed by Joyce himself, but at times I wondered if Joyce’s approval of this book may have been a joke in itself. I’m almost certain that he parodied Gilbert’s pedantic and tiresome style somewhere in Ulysses. This book seems to be mostly a series of long quotations from the novel, which I’m sure were worth including initially since this book was published before Ulysses was available to most readers due to censorship, but it’s repetitive, and Gilbert often doesn’t add much to the text of the novel itself.

It’s hard to resist the idea of a guide to Ulysses endorsed by Joyce himself, but at times I wondered if Joyce’s approval of this book may have been a joke in itself. I’m almost certain that he parodied Gilbert’s pedantic and tiresome style somewhere in Ulysses. This book seems to be mostly a series of long quotations from the novel, which I’m sure were worth including initially since this book was published before Ulysses was available to most readers due to censorship, but it’s repetitive, and Gilbert often doesn’t add much to the text of the novel itself.I try not to get too upset by male chauvinism from other eras (this book was first published in 1930), but it was so blatant here that I can’t avoid a mini-rant. Gilbert starts his chapter on Molly Bloom’s soliloquy with the patronizing statement, “And the comment of the average woman on this, the last episode of Ulysses, is apt to run: 'How true - of that class of woman, with which, thank goodness, I have nothing in common!'” He then quotes another critic’s assessment of Molly’s chapter:

The long unspoken monologue of Mrs Bloom which closes the book . . . might in its utterly convincing realism be an actual document, the magical record of inmost thought by a woman that existed. Talk about understanding ‘feminine psychology’!

I’m glad Gilbert and his buddies seem to have figured out how all women think, apparently just by unlocking the feminine mind with Molly Bloom’s magical key. I like the “Penelope” chapter very much, but not because I think Joyce succinctly sums up the thoughts of all women. Instead he creates a nuanced and multilayered picture of Molly herself. It’s frustrating to read an analysis where the male characters get to be multidimensional individuals, but the female characters (and readers) have to be archetypes and stereotypes. I don’t think that at all reflects what Joyce actually did in Ulysses.

Ranting aside, Gilbert does offer some useful information in his study. He lays out the structural scheme of the novel, breaking down the episodes and their art, colors, symbols, etc. He also expands on the many mythological references. Readers today, though, are lucky enough to have access to the actual novel, which is a lot more fun to read than this book.

I loved Ulysses so much that I'm sad it’s over. Sad also that if I want to read more Joyce, I have to read Finnegans Wake, and that’s not likely to happen any time soon. I’ve been curious about this book since I read A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man in high school years ago. My teacher went on at length about Leopold Bloom’s journey through a day in Dublin as a parallel to Odysseus’s journey home to Ithaca, how a bar of soap in Bloom’s pocket had its own journey to mirror Bloom’s and Odysseus’s, etc. It all sounded both difficult to understand and a little insane, which, now that I’ve finally read it, I think are fair assessments. Books have been written about Ulysses, as well as some excellent reviews on Goodreads, and I’m not going to attempt to review it comprehensively. Instead I want to talk about a couple of things which surprised me about it.

I loved Ulysses so much that I'm sad it’s over. Sad also that if I want to read more Joyce, I have to read Finnegans Wake, and that’s not likely to happen any time soon. I’ve been curious about this book since I read A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man in high school years ago. My teacher went on at length about Leopold Bloom’s journey through a day in Dublin as a parallel to Odysseus’s journey home to Ithaca, how a bar of soap in Bloom’s pocket had its own journey to mirror Bloom’s and Odysseus’s, etc. It all sounded both difficult to understand and a little insane, which, now that I’ve finally read it, I think are fair assessments. Books have been written about Ulysses, as well as some excellent reviews on Goodreads, and I’m not going to attempt to review it comprehensively. Instead I want to talk about a couple of things which surprised me about it. Ulysses is known for its stream of consciousness style (although it is only one of the many styles Joyce employs). At first this style feels random and chaotic, which isn’t surprising, given that there is a certain randomness to the millions of stimuli we process and think about during a day. As the novel progresses, however, it becomes obvious that almost nothing is really random here. Everything from Bloom’s travels, to the things he sees and considers, to the wandering soap is extremely structured. The characters' most minor thoughts, even when they are just little details that are noticed and dismissed in a sentence fragment (Bloom in the Lestrygonians episode noticing food-related things everywhere, for example), are all relevant to the whole.

You can find the Joyce-approved analysis of the novel printed many places and on Wikipedia, which outlines the symbol, art, color and so forth for each chapter, but this isn’t so much what interested me about the structure. The symbolic interpretation didn’t contribute much to the enjoyment of the novel for me. What I found more striking is that the organization is present down to the level of sentence fragments which keep coming back like little melodies that are strange at first, but after frequent repetition start to make sense, and even help anchor the prose. In the Sirens chapter, this is especially apparent. The first few pages are a confusing mess of ideas until you realize that they are phrases from the chapter to come, and then some of those phrases (for example, “Bronze by gold”) reappear later in the novel. Joyce puts the reader in a strange world where very little makes sense at times, but in this huge and complex novel I had the feeling that everything was there intentionally. The structure keeps things from going haywire, and made the novel easier and easier to read the further I got into it.

The other thing I wasn’t expecting was how funny this book was. I even googled “Is Ulysses supposed to be funny,” and felt a little better when I found that Joyce wrote to Ezra Pound complaining that he wished the critics had said how “damn funny” it was. The critics had a lot of other things to talk about, presumably, or maybe Joyce was being ironic, but at any rate, I thought parts of it were hilarious. His parodies and pastiches of prose styles from the Bible to legal and scientific jargon to Dickens to catechistic exposition are dead-on. These are woven into the story without missing a beat. At times he couples those styles with his insane, elephantine lists, like his anthropological style description of a Dublin resident whose “nether extremities were encased in high Balbriggan buskins dyed in lichen purple. . . From his girdle hung a row of seastones which dangled at every movement of his portentous frame and on these were graven with rude yet striking art the tribal images of many Irish heroes and heroines of antiquity” as well as images of at least fifty other people, from Dante Alighieri to Christopher Columbus to Lady Godiva to The Man that Broke the Bank at Monte Carlo. Why Joyce does these things isn’t always clear, but once I got into the spirit of it, it was a lot of fun.

One of the more amusing episodes is the Nausicaa chapter, told from the standpoint of 17 year old Gerty MacDowell in the style of a Victorian romance novel or magazine, but with Gerty’s less admirable thoughts intruding from time to time. Throughout the chapter Gerty’s more earthly musings compete with the high-flown Victorian narrative.

The waxen pallor of [Gerty’s] face was almost spiritual in its ivorylike purity though her rosebud mouth was a genuine Cupid’s bow, Greekly perfect. Her hands were of finely veined alabaster with tapering fingers and as white as lemon juice and queen of ointments could make them though it was not true that she used to wear kid gloves in bed or take a milk footbath either. Bertha Supple told that once to Edy Boardman, a deliberate lie, when she was black out at daggers drawn with Gerty (the girl chums had of course their little tiffs from time to time like the rest of mortals) and she told her not let on whatever she did that it was her that told her or she’d never speak to her again. No. Honour where honour is due. There was an innate refinement, a languid queenly hauteur about Gerty which was unmistakably evidenced in her delicate hands and higharched instep.

Ulysses is notorious for its difficulty, and I did find parts of it tough going. Joyce alludes to a wide variety of topics, so many that probably few modern readers (or even his contemporaries) would catch every one. Joyce seems to know about everything - Greek and Irish mythology, Catholic mass parts, opera, medieval church musical modes, Irish nationalist songs, Irish nationalist history, Hamlet, Yeats, scientific theories, medicine (I think there may have even been a prescription in Latin), not to mention the long list of literary styles he parodies. There were untranslated phrases in at least eight languages I could identify and probably a couple more I wasn’t sure of. These phrases were often in slang or misspelled, probably deliberately.

It all sounds crazy, but with the help of Google Translate, the dictionary, and Wikipedia, it really wasn’t that bad. I did not use a guide or annotated edition because I didn’t want to disrupt reading it too much, but I had a low threshold to look up anything I found confusing. I also referred to Paul Bryant’s wonderful chapter-by-chapter review (http://www.goodreads.com/review/show/6752242) after each episode. I can see why Ulysses is not for everyone. It certainly required more patience and effort than most books, but I thought it was absolutely worth it. And happily I’ll be able to read it several times and keep finding things I’ve missed.

The first volume of this collection of George Orwell’s essays, diaries, and letters covers the period from 1920-1940. During this time, Orwell published seven of his nine books and began to develop the political opinions that would later become so important in his work, but he was still relatively unknown.

The first volume of this collection of George Orwell’s essays, diaries, and letters covers the period from 1920-1940. During this time, Orwell published seven of his nine books and began to develop the political opinions that would later become so important in his work, but he was still relatively unknown. In his letters, he did not mince words about some things he really, really disliked. These included:

Roman Catholics

feminists

Scottish people

vegetarians

fruit-juice drinkers

Oswald Mosley

On the other hand, he generally felt positively about the following:

Ulysses

women

cigarettes

Tropic of Cancer

Revolución!

goats

This collection was edited by Orwell’s widow, Sonia, and Ian Angus. His widow reportedly obstructed many of those who wanted to write his biography. She felt that his work, which was often autobiographical, should stand for itself. She wanted this collection to “read like a novel.” I wouldn’t go that far, but the selection of letters and essays is good, and going back and forth between them does work fairly well. They did cut all the racy parts out of the letters, presumably to avoid embarrassing people involved who may have still been living in 1968 when this was first published.

This is an unusual book, sort of a [b:House of Leaves|24800|House of Leaves|Mark Z. Danielewski|http://d.gr-assets.com/books/1327889035s/24800.jpg|856555] for Orwell nerds. The backstory is that George Orwell’s widow found a partial draft manuscript of [b:1984|5470|1984|George Orwell|http://d.gr-assets.com/books/1348990566s/5470.jpg|153313] and donated it to a charity auction where it sold for £50 in 1952. Years later, Peter Davison, the editor of The Complete Works of George Orwell, obtained access to it and went through the document with painstaking care, publishing it as this book in 1984.

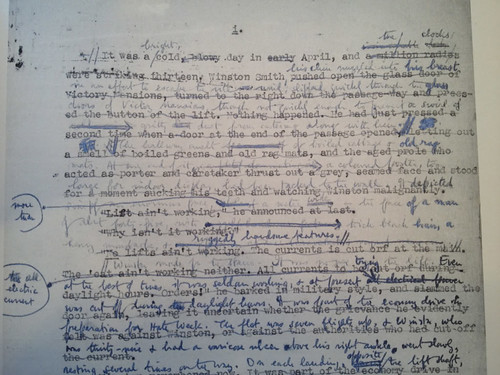

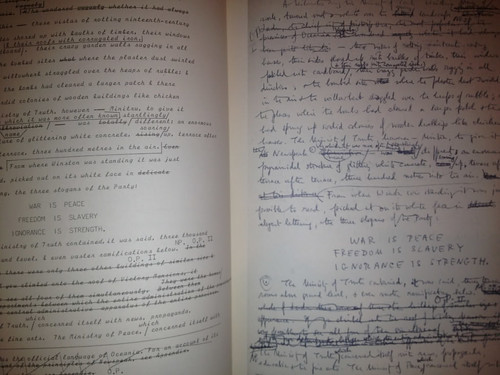

This is an unusual book, sort of a [b:House of Leaves|24800|House of Leaves|Mark Z. Danielewski|http://d.gr-assets.com/books/1327889035s/24800.jpg|856555] for Orwell nerds. The backstory is that George Orwell’s widow found a partial draft manuscript of [b:1984|5470|1984|George Orwell|http://d.gr-assets.com/books/1348990566s/5470.jpg|153313] and donated it to a charity auction where it sold for £50 in 1952. Years later, Peter Davison, the editor of The Complete Works of George Orwell, obtained access to it and went through the document with painstaking care, publishing it as this book in 1984. On the odd-numbered pages, there are facsimiles of the actual manuscript pages. Some of it is type-written, some handwritten, and much of it a confusing mess of both, with lots of crossing-out and writing between lines and in the margins in different colors of ink. The manuscript pages are shown in their actual sizes, which varied as Orwell used several different types and sizes of paper. (I kept expecting to see something scrawled on a napkin or the back of a train ticket, but there was nothing that extreme). On the facing pages, Davison has transcribed the whole thing meticulously, including everything underneath the scribbles, making sense out of it for those whose eyesight isn’t up to the challenge.

The first page of the manuscript - It was a bright, cold day in April and millions of clocks and/or radios were striking thirteen.

Orwell's handwriting on the right with Davison's transcription on the left.

This book gives an insight into Orwell’s writing process for the book he said would have been better if it hadn’t been written “under the influence of TB.” He was very ill for most of the time he was writing it, and even typing was physically difficult for him. There aren’t any big surprises in the actual text, certainly no secret Hollywood happy endings. Orwell changed the year in which the novel is set more than once (1980 crossed out, then 1982, then 1984). There are a few scenes that didn’t make it into the final version, in some cases mercifully, like a bizarre and gruesome lynching that Winston describes when writing about newsreels in his diary. As one would expect with Orwell, many of the edits involve clarifying and simplifying the prose. Some passages that seem relatively straightforward are rewritten five or six times, just in this draft.

This had to be an expensive book to publish. It’s a heavy, oversized hardcover book with different colors of ink and numerous page layouts. The target audience would presumably be small. Still, it’s rare to get a glimpse of a work in progress, since most writers don’t keep multiple manuscript drafts after a book is published (or at least don’t let them be made public). There are no existing manuscripts of Orwell’s other books, and he instructed his literary executor to destroy any drafts of Nineteen Eighty-Four if he died before he finished it. This book would be more of a curiosity to most people, but the effort and scholarship that went into producing it are impressive.

Arthur Koestler had a knack for getting himself locked up. For several years in the 1930s and ‘40s, he took an inside tour of European prisons and concentration camps in Spain, France, and the UK. (Strangely, my edition of this book was published by a travel book publishing company, but I can’t think they would recommend this particular itinerary). Koestler’s friend George Orwell attributed his predilection for incarceration to his “lifestyle,” which is a bit unfair, but there is no doubt Koestler was often in the wrong place at the wrong time. Or maybe the right place from a literary point of view, since he had plenty of life experience from which to draw in writing his most famous novel, Darkness at Noon, about a Russian revolutionary in prison.

Arthur Koestler had a knack for getting himself locked up. For several years in the 1930s and ‘40s, he took an inside tour of European prisons and concentration camps in Spain, France, and the UK. (Strangely, my edition of this book was published by a travel book publishing company, but I can’t think they would recommend this particular itinerary). Koestler’s friend George Orwell attributed his predilection for incarceration to his “lifestyle,” which is a bit unfair, but there is no doubt Koestler was often in the wrong place at the wrong time. Or maybe the right place from a literary point of view, since he had plenty of life experience from which to draw in writing his most famous novel, Darkness at Noon, about a Russian revolutionary in prison.In Scum of the Earth, Koestler recounts his experiences of being interned in a concentration camp in France. Koestler, a Hungarian living in France working as a writer and journalist, was rounded up along with other “undesirables” shortly after France entered the war against Germany in 1939. They were a ragtag group, outcasts who “could be divided into two main categories: people doomed by the biological accident of their race and people doomed for their metaphysical creed or rational conviction regarding the best way to organise human welfare” (p. 93). His fellow prisoners included refugees who had fled from country to country as the German forces advanced across Europe as well as socialists and Communists. Ironically, almost all of them were fiercely anti-Nazi, sometimes much more so than the French police and soldiers they dealt with. Many, including Koestler, were Jewish, and many of them had volunteered to fight in the French army against Germany.

Koestler’s camp, Le Vernet, was one of the more unpleasant ones. Koestler and his fellow ethnic and political outsiders had no legal protection of any kind, with no official charges against them and no due process. They were kept in miserable conditions doing unpaid hard labor. He writes,

“In Liberal-Centigrade, Vernet was the zero-point of infamy; measured in Dachau-Fahrenheit it was still 32 degrees above zero. In Vernet beating-up was a daily occurrence; in Dachau it was prolonged until death ensued. In Vernet people were killed for lack of medical attention; in Dachau they were killed on purpose. In Vernet half of the prisoners had to sleep without blankets in 20 degrees of frost; in Dachau they were put in irons and exposed to the frost” (p. 94).

Koestler points out that the pro-Nazi prisoners in France, who were taken elsewhere, were often treated better due to oversight by the Red Cross and the fear of German retaliation against French prisoners of war. He describes seeing photographs of the conditions for actual Nazi prisoners of war in France, who lived in comparative luxury, “We saw them having a meal in a tidy refectory, and there were tables and chairs and dishes and knives and forks. And we saw them in their dormitory, and they had real beds and mattresses and blankets” (p. 117).

Koestler managed to be released from Le Vernet before France capitulated to Germany, but most were not so lucky. The Gestapo took over the French concentration camps without missing a beat. Helpfully, the French supplied the Gestapo with records and dossiers on the prisoners, so that there was no doubt about their anti-Nazi activities.

Koestler writes vividly of the chaos in France following the capitulation. Caught in a bureaucratic nightmare, he and other undesirable foreigners tried to escape from the country before being captured by the Germans. Many of Koestler’s friends and acquaintances, including fellow writers and intellectuals, commited suicide to avoid being captured. After a lot of complicated maneuvering, Koestler managed to make it to England, where he was promptly imprisoned for six weeks, but at least in relative comfort compared to his experience in France.

Before and during World War II, there was an epidemic of nationalistic and xenophobic feeling. Hitler and Stalin win the dubious prize for infamy with their death camps and gulags, but it was a fairly shameful time in history for “the good guys” as well, with American internment of Japanese-Americans, the concentration and forced labor camps in France described here, and numerous other instances of officially sanctioned persecution of “foreigners” (including citizens of “foreign” descent) in the US, Canada, the UK, and the British colonies. Scum of the Earth provides a disturbing example of how, given the right mixture of xenophobia and national security concerns, a supposedly democratic nation can willingly sacrifice the civil rights, liberties, and due process of its own people and legal visitors.

Someday, maybe I’ll feel up to writing a worthy review of this 20th century masterpiece.

Someday, maybe I’ll feel up to writing a worthy review of this 20th century masterpiece.For now, though, I’ll give the reasons I gave it 4 stars instead of 5:

1. Pedophilia. There is no way around the inherent creepiness of this topic.

2. The road trip. The seemingly endless ride through 1950s Americana did not do it for me. At least no one sang “99 Bottles of Beer on the Wall,” but they might as well have.

3. Eyeball licking.

Those quibbles aside, there is little to equal Nabokov’s playful dexterity with the English language, his nuanced and perceptive depiction of a character who is both truly repulsive and disturbingly charming, and his ability to entertain. Lolita is worth reading for the neologisms alone.

We Die Alone is the story of a Norwegian named Jan Baalsrud who, along with a team of Norwegian commandos trained by the British, sailed in a disguised fishing boat from the Shetland Islands to Norway in a mission to sabotage German forces during World War II. Unfortunately, things go horribly awry, and Baalsrud, the only surviving member of his team, is forced to make a desperate escape through Arctic terrain crawling with German soldiers. In a series of horrific experiences that reads like a cross between Endurance and Touching the Void, Baalsrud faces avalanches, hypothermia, starvation, and being forced to cut off nine of his gangrenous toes with a dull knife. Most remarkable, however, are the scores of Norwegian civilians who help him over the course of his journey at great financial and personal sacrifice, with a very real risk of ruin and death for themselves and their families if they are caught by the German occupation forces.

We Die Alone is the story of a Norwegian named Jan Baalsrud who, along with a team of Norwegian commandos trained by the British, sailed in a disguised fishing boat from the Shetland Islands to Norway in a mission to sabotage German forces during World War II. Unfortunately, things go horribly awry, and Baalsrud, the only surviving member of his team, is forced to make a desperate escape through Arctic terrain crawling with German soldiers. In a series of horrific experiences that reads like a cross between Endurance and Touching the Void, Baalsrud faces avalanches, hypothermia, starvation, and being forced to cut off nine of his gangrenous toes with a dull knife. Most remarkable, however, are the scores of Norwegian civilians who help him over the course of his journey at great financial and personal sacrifice, with a very real risk of ruin and death for themselves and their families if they are caught by the German occupation forces.

This is an enormous doorstop of a book, with over 1,300 pages of George Orwell’s essays. Of course that doesn’t cover everything he wrote, but it’s an awful lot. While best known for his novels Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four, Orwell was probably a better essayist than a novelist. This volume contains Orwell’s best and most famous essays, printed many places (including online), like “Such, Such Were the Joys,” “Shooting an Elephant,” and “Politics and the English Language." It also includes other thought-provoking but harder to find essays like “A Hanging,” and “Notes on Nationalism,” as well as the excellent and still very relevant preface to the first edition of Animal Farm, “The Freedom of the Press.”

This is an enormous doorstop of a book, with over 1,300 pages of George Orwell’s essays. Of course that doesn’t cover everything he wrote, but it’s an awful lot. While best known for his novels Animal Farm and Nineteen Eighty-Four, Orwell was probably a better essayist than a novelist. This volume contains Orwell’s best and most famous essays, printed many places (including online), like “Such, Such Were the Joys,” “Shooting an Elephant,” and “Politics and the English Language." It also includes other thought-provoking but harder to find essays like “A Hanging,” and “Notes on Nationalism,” as well as the excellent and still very relevant preface to the first edition of Animal Farm, “The Freedom of the Press.”As you would expect, there’s plenty here of Orwell’s favorite topics, totalitarianism, fascism, communism, and imperialism, but also much about the little details of everyday life, from how to make the perfect cup of tea to his concept of an ideal pub. This collection has all 80 of the “As I Please” columns that Orwell wrote for the Tribune, a column that can be political but just as often addresses grammar and word choice, attacks clichéd writing, and bemoans the lack of technological advancement in activities such as washing dishes. Orwell wrote many book reviews as well, most of which serve more as a format for him to express his opinions than as a discussion of the books themselves. Sometimes these are on surprising but intriguing topics, such as Orwell's criticism of Tolstoy's criticism of Shakespeare. There are also some funny little gems, like a rant of a letter Orwell wrote in response to a questionnaire he was sent about the Spanish Civil War that begins, “Will you please stop sending me this bloody rubbish” and escalates from there.

This book is organized chronologically, which makes sense, but unfortunately suffers from the lack of an index. Still, for those who want to go beyond the same 10-15 essays that are printed in most anthologies, this edition will provide as many Orwell essays as just about anyone could possibly want to read.

I have always found the Spanish Civil War confusing. After reading Homage to Catalonia, I at least feel that I was justified in my confusion. On the surface, of course, it was a conflict between Franco’s Fascists and the democratic Republican government, but it was far more complicated than that. When Orwell arrived in Spain to fight on the Republican side with the P.O.U.M. militia, a P.S.U.C. position was pointed out to him and he was told “Those are the Socialists” to which he responded, “Aren’t we all Socialists?” He quickly learned that would be far too easy. Orwell does an admirable job of sorting out the alphabet soup of the anti-Fascist parties and militias - the P.S.U.C., C.N.T., F.A.I., P.O.U.M., U.G.T., etc., etc. The distinctions between the Anarchists, left-wing Communists, and right-wing Communists seem subtle, especially since the groups were supposedly united in their opposition to Franco, but they became critically important later. As Orwell learned, associating with the wrong party was a potentially lethal decision.

I have always found the Spanish Civil War confusing. After reading Homage to Catalonia, I at least feel that I was justified in my confusion. On the surface, of course, it was a conflict between Franco’s Fascists and the democratic Republican government, but it was far more complicated than that. When Orwell arrived in Spain to fight on the Republican side with the P.O.U.M. militia, a P.S.U.C. position was pointed out to him and he was told “Those are the Socialists” to which he responded, “Aren’t we all Socialists?” He quickly learned that would be far too easy. Orwell does an admirable job of sorting out the alphabet soup of the anti-Fascist parties and militias - the P.S.U.C., C.N.T., F.A.I., P.O.U.M., U.G.T., etc., etc. The distinctions between the Anarchists, left-wing Communists, and right-wing Communists seem subtle, especially since the groups were supposedly united in their opposition to Franco, but they became critically important later. As Orwell learned, associating with the wrong party was a potentially lethal decision.Orwell served in the P.O.U.M. (Partido Obrero de Unificación Marxista) in 1937. He chose the party somewhat arbitrarily, based on connections he had through the British Independent Labour Party. Homage to Catalonia is far from a comprehensive discussion of the Spanish Civil War. Orwell instead focuses on his personal experiences of fighting at the front (against the Fascists), and then on the May 1937 street fighting in Barcelona, when the various Republican groups fought each other. He vividly describes the experiences of war, with the cold, dirt, and lice, the inadequate weapons, and the idealistic but inexperienced soldiers, some of whom were children. With characteristic dryness, he recounts events such as being shot in the throat by a sniper, beginning, “The whole experience of being hit by a bullet is very interesting and I think it is worth describing in detail.” I would say so.

More interesting, however, is Orwell’s growing disillusionment with the politics of the war, a story he surely did not expect to have to tell when he set out to fight Fascism. He contrasts the atmosphere in Barcelona when he first arrived in Spain, when the workers were in control and he “breathed the air of equality,” with the oppressive environment of the police state that predominated just a few months later. The Soviet-backed P.S.U.C. pinned the May fighting in Barcelona on Orwell’s P.O.U.M., an excuse to suppress the P.O.U.M. and declare it illegal. The P.O.U.M. members were accused of being “Trotsky-Fascists,” which seems like an amusing oxymoron, but with it came the implication that they had secretly aided Franco. This was disastrous for the P.O.U.M. members, many of whom were thrown in jail for months on end without being charged of anything or allowed to stand trial. Many of them “disappeared,” including Andrés Nin, the leader of the P.O.U.M., who met a horrible end at the hands of the NKVD (the Soviet secret police).

Orwell’s commanding officer and friend Georges Kopp was imprisoned in terrible conditions. Orwell recounts a poignant story of frantically rushing around the city trying to convince the authorities to read a letter that would exonerate Kopp. His Spanish was shaky and his voice even weaker after the vocal cord paralysis he suffered from his neck wound. He also ran a very real risk of being arrested himself, simply by association with Kopp and the P.O.U.M. Orwell’s room was raided and all of his books and papers confiscated by the secret police. He and his wife only barely escaped from Spain themselves.

The Spanish Civil War was a microcosm of the conflict that was developing in Europe in the 1930s, a sort of testing ground for ideologies in preparation for World War II. Many foreigners came to fight, idealistically hoping to strike out against Fascism and to support a new government which seemed to represent the working people. Unfortunately, as Orwell came to find, other doctrines were tested as well, with the terrors of the totalitarian police state that came to dominate his later writing.

A Clergyman’s Daughter, George Orwell’s second novel, is the story of Dorothy Hare, the uncomplaining daughter of a selfish, demanding rector. She lives a simple life visiting parishioners and tending to her father’s needs until she inexplicably wakes up one day on the London streets with no idea who she is or how she got there, and without a penny to her name.

A Clergyman’s Daughter, George Orwell’s second novel, is the story of Dorothy Hare, the uncomplaining daughter of a selfish, demanding rector. She lives a simple life visiting parishioners and tending to her father’s needs until she inexplicably wakes up one day on the London streets with no idea who she is or how she got there, and without a penny to her name.This rather contrived plot serves as a framework for a series of essay-like episodes laced with Orwell’s characteristic biting social criticism. The episodes themselves are compelling, from the tedium and pointlessness of a small-town clergyman’s daughter’s routine, dodging the village gossips, to hop-picking in Kent with itinerant workers, to teaching in a horrible “fourth-rate” private school under the mercenary Mrs. Creevy, a headmistress who “never read a book right through in her life, and was proud of it.”

There is also a remarkable scene, written as dramatic dialogue, of Dorothy spending the night out in Trafalgar Square with a group of tramps. This event is a sort of fugue, like a scene from a Broadway musical, with each character presenting his or her situation in parallel. The characters - Dorothy, a defrocked clergyman, a woman kicked out of the house by her husband, and several others - endure a cold, miserable, hungry night while a policeman repeatedly comes by to remind them to go “home” if they want to sleep.

Orwell often appropriates his non-fiction and autobiographical experiences for his novels. In Keep the Aspidistra Flying, for example, Gordon’s drunken jail scene comes almost verbatim from the autobiographical essay, “The Clink,” which also provides material for A Clergyman’s Daughter. Most of the significant episodes in Clergyman can be found in Orwell’s non-fiction, such as his hop-picking diary and his experiences in Down and Out in Paris and London. The school scenes presage the essay “Such, Such Were the Joys.” Here, as in the essay, the primary motive of the school is financial. Dorothy is instructed only to punish the children whose parents aren’t “good payers” because “in private schools the parents’ word is law. Such schools exist, like shops, by flattering their customers, and if a parent wanted his child taught nothing but cat's cradle and the cuneiform alphabet, the teacher would have to agree rather than lose a pupil."

Orwell’s “difficulties with girls,” as Christopher Hitchens called them, are apparent here, and perhaps it is his unease with working with his only female protagonist that weakens this novel. Dorothy is a far more sympathetic character than John Flory or Gordon Comstock, but she lacks dimension. Bad and good things seem to happen to her without her exerting much influence on the world around her. Flory, Gordon, and Winston Smith all attempt to influence their worlds; Dorothy is merely reactive.

Dorothy suffers unwelcome advances from the good-natured but lecherous Mr. Warburton just prior to her mental break. His behavior is fairly repulsive, sneaking up behind Dorothy, while telling her he considerately chose this approach so she would be spared his unattractiveness. Warburton has no qualms about his actions and isn't at all bothered by Dorothy’s distress.

Apparently this scene between Warburton and Dorothy was to have been an attempted rape, but had to be changed due to concerns about obscenity. That certainly explains the general creepiness of the scene, which otherwise seems out of proportion to Warburton’s actions. One of the major structural flaws in this novel is Dorothy’s amnesia, which seems to come out of nowhere. Reaction to the psychological trauma of an attempted rape would have made that more believable.

After this unpleasant episode, Orwell-as-narrator gives a snarky aside, essentially about the frigidity of “educated” women, that is unfair to Dorothy and out of place with what is otherwise a sympathetic portrayal. (Hopefully this remark was written after the rape scene was changed, because otherwise it would have been a really nasty thing to say.) This comment seems to reflect more Orwell’s issues with women, which are well-documented, than Dorothy’s failings.

The novel does, however, give a detailed presentation of the extremely limited options for a woman in Dorothy's social situation. She has no good options other than acting as a servant for her selfish father. When she passed up marriage prior to the events of the novel, she seemingly doomed herself to an extremely dreary future. When Dorothy is on the street she has an even more difficult time than men in the same situation. As a single woman she can't even rent a room because of landladies suspicious of prostitutes. While we as the readers see these problems, Dorothy herself doesn’t seem to have a lot of thoughts about them. It wouldn’t be fair to say that Orwell doesn't “get” women's issues; he seems to get the issues intellectually, but falls short at incorporating them into his protagonist’s temperament.

A Clergyman’s Daughter is the weakest of Orwell’s novels. He wasn’t proud of it, admitting that he published it because he needed the money. It would hardly be considered essential 20th century literature, but it is interesting to see how Orwell works with ideas that appear repeatedly in his essays and other books - experiences with education, religion, and the indigent, as well as interesting thoughts on the loss of religious faith. There are many good elements here, with excellent writing in some scenes. The story, however, is subjugated to the social commentary, preventing this work from being a cohesive novel.

Girl problems, money problems, houseplant problems. Things are not going Gordon’s way. Money has become Gordon Comstock’s all-consuming idée fixe (followed closely by aspidistras). Gordon, who comes from “one of those depressing families, so common among the middle-middle classes, in which nothing ever happens,” refuses to be a slave to the “money-god.” He gives up a relatively well paying but soulless job at an advertising agency, a job that furthers the evils of the capitalism that he deplores. He instead deliberately seeks out a position in a bookshop with low pay and no hope of advancement while he struggles at writing his poetry.

Girl problems, money problems, houseplant problems. Things are not going Gordon’s way. Money has become Gordon Comstock’s all-consuming idée fixe (followed closely by aspidistras). Gordon, who comes from “one of those depressing families, so common among the middle-middle classes, in which nothing ever happens,” refuses to be a slave to the “money-god.” He gives up a relatively well paying but soulless job at an advertising agency, a job that furthers the evils of the capitalism that he deplores. He instead deliberately seeks out a position in a bookshop with low pay and no hope of advancement while he struggles at writing his poetry.At first this decision may appear noble and idealistic, but Gordon rapidly ceases to be a sympathetic character as he mooches money off of his long-suffering and far from wealthy sister and complains nonstop to everyone who will listen about both the evils of money and how difficult it is for him not to have money. As he points out, he isn’t poor enough to experience actual hardship (unlike many in the 1930s), but is poor enough that everything from socializing with friends to courting his girlfriend to writing poetry to having a cup of tea without having to hide it from the landlady is nearly impossible.

His lack of money, which is at least partially self-inflicted, becomes Gordon’s excuse for all that he has failed to achieve in his life. His endless whining is so pervasive that you want to shake him. Gordon is hardly the most charming of protagonists, but his tragic fall and relationship with his saintly girlfriend, Rosemary, are still compelling, largely due to Orwell’s vivid characterizations.

Keep the Aspidistra Flying is not nearly as aggressively political as Orwell’s more famous works. The novel is more concerned with interpersonal relationships, but still addresses the larger issues of capitalism, socialism, and class division in a darkly humorous manner.

Poor Flory. If only he'd had the good sense to be born into an E.M. Forster novel instead of one by George Orwell, he might have had half a chance.

Poor Flory. If only he'd had the good sense to be born into an E.M. Forster novel instead of one by George Orwell, he might have had half a chance.Burmese Days, Orwell’s second book, draws on his own experiences as a police officer in imperial Burma in the 1920s. The novel describes the experiences of John Flory, an English timber merchant living in a Burmese outpost. Flory feels increasingly estranged from the other Europeans. His only real friend is a Burmese doctor, despite the disapproval of his fellow Englishmen. Flory finds their overt racism repulsive, though his rebellion against it is halfhearted.

Flory deals with his sense of alienation as many of his fellow Europeans do, comforting himself with a Burmese mistress and vast quantities of gin. When the lovely but vapid Elizabeth Lackersteen arrives on the scene, Flory thinks he has found a kindred spirit to rescue him from his isolation. He misreads her utterly, however, resulting in some truly cringe-inducing scenes of courtship. And just in case Flory weren’t inept enough in the love department already, he gets some help when the complicated plotting of a corrupt Burmese magistrate turns him into collateral damage.

Burmese Days is a scathing attack on racism and imperialism that seems in many ways ahead of its time. The novel was published in the United States before it was published in the U.K. because it was thought that it would be more palatable in a country without a direct connection to colonial India and Burma (and where the real-life models for the characters wouldn’t be recognized).

It often feels like much of Orwell’s work, both his novels and essays, served as a lifelong preparation for Nineteen Eighty-Four. This is true even in Burmese Days, with a setting that little resembles Oceania. Still, the theme of isolation and repression of thought is strong:

"It is a stifling, stultifying world in which to live. It is a world in which every word and every thought is censored. In England, it is hard to imagine such an atmosphere. Everyone is free in England; we sell our souls in public and buy them back in private, among our friends. But even friendship can hardly exist when every white man is a cog in the wheels of despotism. Free speech is unthinkable. All other kinds of freedom are permitted. You are free to be a drunkard, an idler, a coward, a backbiter, a fornicator; but you are not free to think for yourself. Your opinion on every subject of any conceivable importance is dictated for you by the pukka sahibs' code . . . it is a corrupting thing to live one's real life in secret. One should live with the stream of life, not against it."

Despite these serious themes, Burmese Days is still an engaging story. Admittedly, most of the characters border on loathsome, painted with Orwell’s extremely dry wit. Hopefully some of them are exaggerated caricatures, but unfortunately many probably aren’t. Flory, though, despite his numerous failings, still has a certain poignant appeal. Though the odds are stacked greatly against him, it’s hard not to hope he can somehow prevail.

Alec Waugh (older brother of the more famous Evelyn) wrote this semi-autobiographical novel about a fictional British public school over a six week period when he was 17 years old and doing military training during World War I. It's a school story in the tradition of Tom Brown's Schooldays, but updated for the pre-war generation. Unlike Tom Brown, The Loom of Youth contains several pointed criticisms of the public school system. It was controversial at the time for those criticisms, and also for the discussion of homosexual activity between schoolboys. That discussion was enough to get Waugh kicked out of his school's "old boy" alumni club after the book was published, but to a modern reader it's more in the vein of blink-and-you-miss-it (I did miss it - I was into the next chapter before I realized what they had been talking about).

Alec Waugh (older brother of the more famous Evelyn) wrote this semi-autobiographical novel about a fictional British public school over a six week period when he was 17 years old and doing military training during World War I. It's a school story in the tradition of Tom Brown's Schooldays, but updated for the pre-war generation. Unlike Tom Brown, The Loom of Youth contains several pointed criticisms of the public school system. It was controversial at the time for those criticisms, and also for the discussion of homosexual activity between schoolboys. That discussion was enough to get Waugh kicked out of his school's "old boy" alumni club after the book was published, but to a modern reader it's more in the vein of blink-and-you-miss-it (I did miss it - I was into the next chapter before I realized what they had been talking about).The story is light on plot and heavy on cricket and rugby football. I will admit that the cricket and rugby went way over my American head. The story meanders a bit (Waugh tells us in the preface that he sent it chapter by chapter to his publisher father for proofreading and never did any revisions). The characters, however, are engaging and the story entertaining.

Waugh's protagonist struggles with ambivalence, enjoying his school days but recognizing the flawed system's inability to prepare him for life afterwards. As the characters draw closer to war, these concerns about educational quality become more pertinent. The schoolmasters urge on the boys, asking how they can expect to do well fighting in the trenches if they don't take football seriously enough. With the hindsight of knowing what history will bring, these situations are unsettling, but the characters (and probably the author as well, who had not yet been to the front when he wrote this) seem to have just a glimmer of what's in store for them and their generation. The mood of the novel is lighthearted overall, depicting a very particular place and time with a generation on the eve of war, but not yet colored much by it.

In We Will Not Cease, Archibald Baxter recounts his experiences as a conscientious objector during World War I. Baxter was a New Zealand farmer who had no “official standing” as a conscientious objector because he did not belong to any particular pacifist religious sect. Initially imprisoned by New Zealand authorities, Baxter and thirteen others were eventually sent to the front in France. Baxter steadfastly stuck to his belief that all war is wrong, refusing to follow military orders or to take any kind of non-combat role.

In We Will Not Cease, Archibald Baxter recounts his experiences as a conscientious objector during World War I. Baxter was a New Zealand farmer who had no “official standing” as a conscientious objector because he did not belong to any particular pacifist religious sect. Initially imprisoned by New Zealand authorities, Baxter and thirteen others were eventually sent to the front in France. Baxter steadfastly stuck to his belief that all war is wrong, refusing to follow military orders or to take any kind of non-combat role. [a:Bertrand Russell|17854|Bertrand Russell|http://d.gr-assets.com/authors/1357460876p2/17854.jpg], probably Britain’s most famous pacifist of the day, got off easy with just imprisonment in comparison to Baxter’s experiences. While many of the enlisted soldiers were kind to Baxter, he faced treatment from New Zealand and British army officers that ranged from indifferent to barbaric. When he refused to wear an army uniform, his hands were cuffed behind his back for three weeks straight. He was denied treatment for a toothache unless he agreed to serve. At one point he was given nothing to eat for several days. He had no money to buy food, since he received no pay, and he had to depend on a kindly cook to keep from starving. He was deliberately placed in a location undergoing heavy shell fire from German artillery and ordered not to move. Throughout all of this he was repeatedly reminded that he could be executed at any time.

Baxter was also placed on the notorious Field Punishment No. 1, the “crucifixion” punishment used for recalcitrant soldiers during WWI. While guidelines indicate that this punishment was to be used for only two hours a day, Baxter spent upwards of three to five hours a day, every day, tied to a post for almost a month, even during a blizzard. He describes it:

"The ropes...cut into the flesh and completely stopped the circulation. When I was taken off my hands were always black with congested blood. My hands were taken round behind the pole, tied together and pulled well up it, straining and cramping the muscles and forcing them into an unnatural position...The slope of the post brought me into a hanging position, causing a large part of my weight to come on my arms, and I could get no proper grip with my feet on the ground, as it was worn away round the pole and my toes were consequently much lower than my heels. I was strained so tightly up against the post that I was unable to move body or limbs a fraction of an inch. Earlier in the war, men undergoing this form of punishment were tied with their arms outstretched. Hence the name of crucifixion. Later, they were more often tied to a single upright, probably to avoid the likeness to a cross. But the name stuck."

Field Punishment No. 1, a somewhat milder form than that used with Baxter (From Library and Archives Canada)

Baxter steadfastly maintained his beliefs under these conditions, patiently answering endless questions as to why he was holding out. Sometimes these questions were asked with genuine curiosity, sometimes they were accompanied by beatings, but he never wavered, stating:

"I object to Governments forcing the people of a country under conscription to murder the people of another country. I am making my protest against it in the best way I can. War is an evil thing, should be done away with, and I believe can be done away with. It seems right to me to stand out against it and I intend to stand out against it, no matter what I suffer, even if they kill me."

Whatever your feelings about Baxter’s political views, it’s hard not to be impressed with his unflinching commitment. Persecuting Baxter and his fellow conscientious objectors with such bizarre zeal served no useful purpose and only diminished those who mistreated them. It is ludicrous that so much effort would be expended over the beliefs of a few men in the midst of the global insanity that was World War I.

(A free online copy of this book can be found at the New Zealand Electronic Text Centre)