50

Followers

44

Following

sarahsar

Goodreads refugee (http://www.goodreads.com/user/show/1257768-sarah) exploring BookLikes.

A readable treatment of a complex, hotly debated subject, but the use . . . of ellipses. . . is distracting.

A readable treatment of a complex, hotly debated subject, but the use . . . of ellipses. . . is distracting.

“From the Halls of Montezuma,

“From the Halls of Montezuma,To the shores of Tripoli,

We fight our country's battles

In the air, on land, and sea.”

--The Marines’ Hymn

The Pirate Coast tackles the story of the fledgling United States’ first foreign war, a conflict with the country formerly known as Tripoli (now Libya). By the early days of the United States, the Barbary pirates had a long history of making a nice living from piracy. Operating out of Tripoli, Tunis, and Algiers, they were the scourge of the Mediterranean, capturing ships, stealing their cargo, and holding the passengers for ransom or selling them as slaves. The Barbary states were able to bring in a steady income as tribute from from other countries. Refusal to pay the tribute would put foreign vessels at risk of falling prey to the pirates.

William Bainbridge paying tribute to the Dey of Algiers (Source: Wikipedia)

President Jefferson refused to pay the tribute, and Tripoli declared war on the United States. In October 1803, an American ship under the leadership of Captain William Bainbridge was blockading Tripoli when it was captured. More than 300 Americans were made slaves. For almost two years, they lived under harsh conditions, with physical abuse, small quantities of poor food, and difficult work. Yussef Karamanli, the Dey (ruler) of Tripoli, hoped that such treatment would result in complaints back to the U.S., hopefully driving up the ransom. His scheming had an impact - Americans back at home, perhaps somewhat hypocritically, were horrified at the idea of white Christian Americans serving as slaves to Muslim oppressors.

Enter William Eaton, army officer and former consul to Tunis. Irascible but principled, Eaton led his Marines on a difficult mission to bring the Yussef’s ousted brother, Hamet, across the desert to Tripoli with the objective of inciting civil war and replacing the recalcitrant and demanding Yussef with the more cooperative, though regrettably weaker, Hamet.

William Eaton (Source: Wikipedia)

Eaton made a good showing, capturing the city of Derne and placing the U.S. in an excellent position to negotiate a favorable treaty. Unfortunately, poor communications and weak diplomacy undermined what could have been an impressive military victory. Despite American pronouncements on entering the war, the United States eventually ended up paying to ransom the slaves and even agreed to objectionable tributes, a condition that would last until the Second Barbary War in 1815. Even more disgraceful in Eaton’s eyes, the U.S. did not manage to negotiate freedom for Hamet’s wife and children (who had been the brother Yussef’s hostages for years), and left Hamet in an extremely uncomfortable situation after his failed coup. Eaton never forgave Tobias Lear, who negotiated the treaty, or Thomas Jefferson for betraying promises to Hamet and tarnishing the American reputation in that region.

Overall, it was an inauspicious start for U.S. foreign affairs. Despite Jefferson’s inaugural vow to avoid “entangling alliances” with other nations, it proved easier said than done. Fomenting civil war in another country turned out to be trickier than anticipated. The discussion afterwards as to what the U.S. had and had not actually agreed to, while the participants worked on spinning a more favorable version of the story and political opponents seized the opportunity to take advantage of it, did none of them any credit. It's funny what a hard lesson that is to learn.

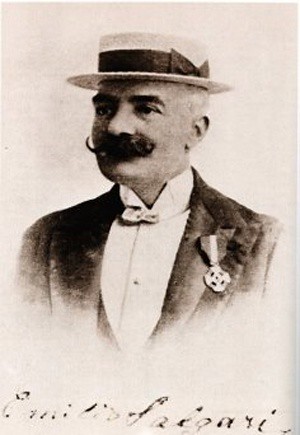

In the process of working on my Italian language skills, I found this book by Emilio Salgari. Salgari was one of the best-selling Italian writers of all time. While almost unheard of in English-speaking countries, his style of adventure writing inspired numerous films, and some consider him the “Grandfather of the Spaghetti Western.”

In the process of working on my Italian language skills, I found this book by Emilio Salgari. Salgari was one of the best-selling Italian writers of all time. While almost unheard of in English-speaking countries, his style of adventure writing inspired numerous films, and some consider him the “Grandfather of the Spaghetti Western.”

Emilio Salgari

[b:Il corsaro nero|78842|Il corsaro nero|Emilio Salgari|http://d.gr-assets.com/books/1315788575s/78842.jpg|76128] (“The Black Corsair”) is an adventure novel published in 1898. It is probably aimed at the vocabulary and interests of an eleven year old boy (which seems about right for my Italian level and attention span). The story, set in the 1600s, follows the adventures of the Black Corsair, a dread pirate set on avenging the deaths of his brothers (the Red Corsair, the Green Corsair, and a non-pirate brother).

The Pirates of the Caribbean owe a debt to Salgari’s stories

The Black Corsair’s brothers were executed by the cruel Governor of Maracaibo, Wan Guld. The surviving brother pursues his vendetta against the Governor with a tenacity that borders on the unhinged, swearing an oath to kill the Governor and everyone related to him. In the process, he and his companions face off against just about every challenge imaginable on the sea and in the jungle - a torrential hurricane, poisonous snakes, a snake charmer, jaguars, vampire bats, quicksand, duels of honor, bloody raids (based on historical events) on Maracaibo and Gibraltar, Venezuela, and, of course, a beautiful Flemish duchess captured in a sea battle who just happens to have a mysterious background. (There’s no way that could go wrong). All in all, it’s good fun.

In The Glass-Blowers, Daphne du Maurier explores her French family background through historical fiction, much as she did for another branch of her family in [b:Mary Anne|149712|Mary Anne|Daphne du Maurier|http://d.gr-assets.com/books/1333331487s/149712.jpg|2186383]. In this novel, the stormy backdrop is the French Revolution. Du Maurier’s forbears, the Bussons (du Maurier was later added as an affectation by one of the brothers), were a family of master craftsmen in the art of glassblowing.

In The Glass-Blowers, Daphne du Maurier explores her French family background through historical fiction, much as she did for another branch of her family in [b:Mary Anne|149712|Mary Anne|Daphne du Maurier|http://d.gr-assets.com/books/1333331487s/149712.jpg|2186383]. In this novel, the stormy backdrop is the French Revolution. Du Maurier’s forbears, the Bussons (du Maurier was later added as an affectation by one of the brothers), were a family of master craftsmen in the art of glassblowing.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Glassblowing, of course, is an apt metaphor for the Revolution itself. “Control is of supreme importance. One false movement and the expanding glass will be shattered . . . There comes this supreme moment to the glass-blower, when he can either breathe life and form into the growing bubble slowly taking shape before his eyes, or shatter it into a thousand fragments.”

Du Maurier chooses to examine the French Revolution from a slightly unusual perspective. The story of Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette is peripheral. Nor is this Dickens’ depiction of oppressed Parisian peasants exacting revenge with the guillotine. In The Glass-Blowers, the story takes place primarily outside Paris, in smaller towns and in the countryside. The narrator, Sophie, describes her family’s position in the glass-making business, as well as the revolutionary activities of two of her brothers and a sister. Another brother, Robert (Daphne’s future great-great grandfather), eventually flees to England to escape his creditors, earning the shameful label of émigré, an epithet which carries overtones of treason to the Republic.

The other two brothers become local leaders, enjoying their elevated status in the new Republic. They decide when to loot a chateau or execute or imprison those who seem suspicious to the new regime. They experience their own misfortunes, however, in the general chaos. The depiction of the family’s encounter with the Vendéans is particularly chilling. This violent side note in a country simultaneously torn by revolution and involved in a foreign war doesn’t get as much attention in the era’s history as other events. The Vendéans were an enormous mob of Royalist soldiers, peasants (including women and children), dispossessed aristocracy, and clergy that advanced from the Vendée region against the French Republic. Du Maurier describes how they occupied and looted houses during a stop in Le Mans, by that time desperate and starving, and were then repulsed by the Republican forces, in many cases annihilated down to the last man, woman, and child.

Du Maurier’s viewpoint on all of these events is a personal one, giving an idea of the day-to-day existence of people trying to live what would otherwise be ordinary lives in the midst of tumultuous upheaval. In such a turbulent time, even the lives of ordinary people make compelling novels.

(This review refers to the Italian translation)

(This review refers to the Italian translation)Operating on the principle that l'ignoranza non è forza, I wanted to read some books in Italian before taking a trip to Italy in a few months. My Italian is rusty, to put it mildly. 1984 may seem like a strange choice of Italian reading material unless maybe it's for a Celebrity Death Match?, but I found an ebook version of it and figured since I’ve read it a gazillion times, it wouldn’t matter too much if I occasionally got lost. The syntax is straightforward, which helps (believe me, I am not ready for Umberto Eco). My husband thought I was a little crazy to read this, but wait until we get to Italy and he wants to order a glass of Victory Gin. Who’s going to have the last laugh then?

I found the translation feature on the Kindle to be very useful for reading in a second language. You can load a translation dictionary so that when you touch a word in the book you're reading, you get its translation. If a translation isn’t available, it defaults to a standard dictionary in the book’s language. Sometimes that’s even preferable, since it doesn’t take your mind out of the language you're working in. I found that on average I probably looked up about as many words per page as I did for [b:Ulysses|338798|Ulysses|James Joyce|http://d.gr-assets.com/books/1346161221s/338798.jpg|2368224], which is, ostensibly, in English.

As far as the quality of the translation goes, I don’t think my Italian is good enough to be too critical. I thought Manferlotti did a good job with Newspeak, especially with the fictional appendix at the end. It’s a tricky thing to convey the sense of Newspeak in a language other than English, but it worked well.

One quibble - I thought the use of the word topo for “rat” was strange, especially given its importance to the story. That word makes me think of Mickey Mouse (“Topolino”), like in these comic books similar to those I remember at my grandparents' house years ago:

The word ratto seems a lot closer to 1984’s not-so-benign rodent, which I picture more like this charming guy:

Imagine that you and your former high school boyfriend or girlfriend parted amicably or maybe not so amicably* many years ago. You lost track of that once central person in your life after high school. He/she went overseas for a few years, changed his/her name, and unbeknownst to you became a world-famous author. When you discovered this, you exchanged a few letters shortly before that person’s untimely death. Then, sixty or so years after your childhood romance, after scores of others had written biographies, you decided you might as well write a book about your old flame, because no one else could really know him/her as you had.

Imagine that you and your former high school boyfriend or girlfriend parted amicably or maybe not so amicably* many years ago. You lost track of that once central person in your life after high school. He/she went overseas for a few years, changed his/her name, and unbeknownst to you became a world-famous author. When you discovered this, you exchanged a few letters shortly before that person’s untimely death. Then, sixty or so years after your childhood romance, after scores of others had written biographies, you decided you might as well write a book about your old flame, because no one else could really know him/her as you had. That scenario is the basis of Eric and Us, Jacintha Buddicom’s odd little memoir of her relationship with Eric Blair, later to be known as George Orwell. The Blairs and Buddicoms were neighbors in the village of Shiplake, and young Eric and Jacintha were childhood friends. Buddicom paints an idyllic picture of life in Edwardian/Georgian England, full of fishing trips and parlor games. She describes the young Orwell as bright, happy, and determined to be a FAMOUS AUTHOR from a young age. He stands on his head to get the attention of Jacintha and her siblings, writes poems for her, and gives her books (including a copy of [b:Dracula|17245|Dracula|Bram Stoker|http://d.gr-assets.com/books/1347251549s/17245.jpg|3165724], accompanied by a carefully wrapped crucifix and clove of garlic).

Buddicom is proprietary about her memories of Orwell, becoming irritable about those who have created a “mystique” surrounding him that doesn’t fit with her recollections. She is oddly defensive about Orwell’s claims of unhappiness at boarding school in his essay Such, Such Were the Joys, going point by point to refute him (nobody got caned all that much, the rich boys weren’t really Scottish millionaires, he wasn’t really ugly or smelly, he wasn’t that poor). It seems like a strange fight to pick. While Orwell may have exaggerated his miseries at St. Cyprian’s in his essay, Buddicom wouldn’t necessarily have been in a position to know. It doesn’t seem to have occurred to her that he could have experienced inner distress that he didn’t choose to talk about on school vacations. She writes, “In Such Such Were the Joys we hear the voice of the sick and disappointed man of forty-three: not the voice of the good-humoured schoolboy of fourteen” (53). Undoubtedly Orwell’s essay could have been colored by time and subsequent events, as could have Buddicom’s rosy memories.

Buddicom seems most offended by Orwell’s books. While she liked [b:Animal Farm|7613|Animal Farm|George Orwell|http://d.gr-assets.com/books/1327872845s/7613.jpg|2207778] and [b:Burmese Days|9650|Burmese Days|George Orwell|http://d.gr-assets.com/books/1166031282s/9650.jpg|1171545], she was “shocked” by [b:Homage to Catalonia|9646|Homage to Catalonia|George Orwell|http://d.gr-assets.com/books/1337103046s/9646.jpg|2566499], about Orwell’s experiences in the Spanish Civil War, saying, “It is impertinence for independent members of a different nationality to interfere with the internal affairs of a country not their own” (154). She can’t understand how Dorothy in [b:A Clergyman's Daughter|319238|A Clergyman's Daughter|George Orwell|http://d.gr-assets.com/books/1348227755s/319238.jpg|1469726] ends up in the company of tramps, a situation she calls “utterly revolting” (136). Buddicom may have seen Julia in [b:1984|5470|1984|George Orwell|http://d.gr-assets.com/books/1348990566s/5470.jpg|153313] as being vengefully modeled on her. Speaking of his novels, she laments, “If only one of them could have had, if not a happy, at least an encouraging ending” (155).

Jacintha Buddicom presents an insight into George Orwell’s youth from a perspective not available elsewhere, but her viewpoint is slightly tilted. She sees his life and work through a very particular prism, as if his life stopped in 1922 and picked up again in 1949, without any intervening world or life events. Buddicom must have wanted him to have had a happier childhood and written happier books (preferably without the pesky politics) than he did. She would not be the first to project an agenda or ideology onto Orwell’s work, in what she called the “Orwell Mystique.” But it seems strange in someone who knew him so well.

*I read the first edition of this book, the one without the notorious postscript by Dione Venables, Jacintha Buddicom’s cousin. The postscript, published after Buddicom’s death, describes an encounter between Orwell and Buddicom that was anything from a "botched seduction" to attempted rape. Depending on the biographer, this event may have been the precipitating event that led to Orwell moving to Burma rather than pursuing a university education. It’s a far from clear-cut scenario, with Venables writing rather fancifully of Jacintha as Orwell’s "muse", and Buddicom herself saying, “...among all the boys we knew, Eric was one of the most interesting, the best-informed, the kindest, the nicest” (143). If the story is accurate, those descriptions hardly seem apt, but it may explain the odd undercurrent of ire in this book.

This is a book that I don’t think I would have read if it weren’t for Goodreads. I probably would never have even heard of it. Technically, I suppose this obscure novel would be considered “historical fiction,” but that’s misleading. It is that, but it is also biography, philosophy, meditation, poetry.

This is a book that I don’t think I would have read if it weren’t for Goodreads. I probably would never have even heard of it. Technically, I suppose this obscure novel would be considered “historical fiction,” but that’s misleading. It is that, but it is also biography, philosophy, meditation, poetry.Hadrian was Emperor of Rome from AD 117 to 138. Marguerite Yourcenar wrote this novel in the form of a memoir, written by Hadrian near the end of his life and addressed to then 17-year old future emperor Marcus Aurelius. Hadrian discusses his public role and his attempts to use diplomacy more than bloodshed. By the standards of the Roman Empire, his reign was considered peaceful (this in spite of a war with the Jews resulting in hundreds of thousands of deaths and the banishment of the Jewish people from Jerusalem).

Most of the emperor’s recollections, however, focus on the personal, even the trivial. He reflects on moderation in diet, his love of hunting, and his admiration for Greek culture. With a reserved tone that belies his depth of feeling, he relates his love for the young Bithynian, Antinous, and his sorrow at Antinous’ death. Hadrian deals with his grief by deifying the youth and creating a cult which long outlasts them both. There must be hundreds of statues of Antinous in the world’s museums today, a testament to an emperor’s attempt to cope with a very personal sorrow.

Antinous

Yourcenar seems to channel this character of antiquity, speaking with an authentic dignity and distance that is not modern in feel. Hadrian speaks to us, but not in a tell-all confessional. In her notes on the writing of the novel, Yourcenar quotes from Flaubert about the period when Hadrian lived, “Just when the gods had ceased to be, and the Christ had not yet come, there was a unique moment in history, between Cicero and Marcus Aurelius, when man stood alone.” Her Hadrian is a man of that age, not ours.

The mood of this book is quiet, thoughtful, and peaceful. It evokes the feeling of walking among ancient ruins, with the eerie sensation that comes when other tourists are out of view, as the warm Italian sun gleams off fragments of stone, and for a moment there is a strange perception that the ruins are whole again, with time somehow distorted.

Hadrian's Villa, Tivoli

1

1

I've been on an ancient Roman kick lately, and I liked [b:Darkness at Noon|30672|Darkness at Noon|Arthur Koestler|http://d.gr-assets.com/books/1290053535s/30672.jpg|881601], so how could I resist reading Arthur Koestler's The Gladiators? Especially when I found a used copy of it with this incredible cover. There are scantily clad dancing girls in the background and half (mostly?) naked men going at each other with swords and tridents. Plus an oddly Old Western font for the title.

I've been on an ancient Roman kick lately, and I liked [b:Darkness at Noon|30672|Darkness at Noon|Arthur Koestler|http://d.gr-assets.com/books/1290053535s/30672.jpg|881601], so how could I resist reading Arthur Koestler's The Gladiators? Especially when I found a used copy of it with this incredible cover. There are scantily clad dancing girls in the background and half (mostly?) naked men going at each other with swords and tridents. Plus an oddly Old Western font for the title.

Unfortunately, the book does not live up to the promising cover art. Koestler's tale covers the slave rebellions of 73-71 BC, led by Spartacus, a gladiator. The historical events were sensational enough in their own right. The army of slaves, eventually growing to more than 100,000, survived events such as a siege inside Mount Vesuvius to defeat Roman legions and capture several towns. Rome did not take the uprising seriously at first, but eventually was forced to send out armies led by Crassus and Pompey to crush it. If it hadn’t been for some double-crossing pirates, Spartacus may have escaped, but he was eventually killed in battle. Thousands of survivors of the slave army were crucified for 200 miles along the Appian Way.

Stanley Kubrick's Spartacus, better clothed than Koestler's

It’s a compelling story, and certainly fits with Koestler’s theme of failed revolution. He uses this theme to tie together a trilogy that includes [b:The Gladiators|2425371|The Gladiators|Arthur Koestler|http://d.gr-assets.com/books/1330389604s/2425371.jpg|2178804] (published in 1939), [b:Darkness at Noon|30672|Darkness at Noon|Arthur Koestler|http://d.gr-assets.com/books/1290053535s/30672.jpg|881601] (1940), and [b:Arrival and Departure|1714864|Arrival and Departure|Arthur Koestler|http://d.gr-assets.com/books/1187303064s/1714864.jpg|611584] (1943), three books on different topics, but all about aspects of revolutions gone wrong.

It’s in the philosophizing, though, where Koestler goes awry. He frequently interrupts the action for the characters to engage in long conversations about economics, unemployment, and government. These conversations seem more appropriate to a 1930s Parisian coffee house than a tent on the eve of a famous battle of antiquity, especially when sprinkled with terms like “proletariat.” There are oblique references to Christian themes like resurrection that are not really explored. These allusions end up seeming anachronistic. The characters’ motivations remain obscure, and it’s hard to sympathize with the oppressive Romans or the raping and plundering slave army. The Gladiators is part history, part fiction, and part allegory, but doesn’t really succeed at any of these.

Robert Graves gives this work of historical fiction an intriguing premise. He presents Jesus not as the offspring of a divine being, born of a virgin birth, but as the very mortal son of Mary and Antipater, the eldest son of King Herod the Great. Herod had a nasty tendency to eliminate family members who crossed him without much of a hearing. Antipater fell victim to this paranoia, and was executed just before Herod’s death. Antipater’s death left Jesus as the rightful heir to the terrestrial kingdom of Judaea, based on his descent from Herod. Mary’s descent from the House of David just served to solidify Jesus’s position.

Robert Graves gives this work of historical fiction an intriguing premise. He presents Jesus not as the offspring of a divine being, born of a virgin birth, but as the very mortal son of Mary and Antipater, the eldest son of King Herod the Great. Herod had a nasty tendency to eliminate family members who crossed him without much of a hearing. Antipater fell victim to this paranoia, and was executed just before Herod’s death. Antipater’s death left Jesus as the rightful heir to the terrestrial kingdom of Judaea, based on his descent from Herod. Mary’s descent from the House of David just served to solidify Jesus’s position.

King Herod the Great/Wicked - Grandfather of Jesus? (Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Jesus didn’t learn any of this until much later, of course, and grew up thinking Joseph the carpenter was his father. He is depicted as initially a scriptural prodigy, then later a man of great learning, a philosopher, a charismatic speaker, and a prophet. Arguably he fulfills several of the different Messianic prophecies, but Graves’s Jesus does not put himself forward as the Son of God.

Graves is at his best in discussing the circumstances of Jesus’s arrest and trial. He knows his Roman politics, and this section reads like it could be a chapter of [b:I, Claudius|18765|I, Claudius (Claudius, #1)|Robert Graves|http://d.gr-assets.com/books/1348245799s/18765.jpg|4232388]. Judas gets a sympathetic portrayal, appearing to be a victim of political manipulation rather than a traitorous tool of Fate. Pontius Pilate is a sly political schemer, and he can’t quite get off the hook by placing the blame for Jesus’s death on Jewish elders. He has too much at stake, with the implications that a Jesus as King of the Jews/Israel would have for the Roman Empire. As Pilate sees it from his own purely selfish viewpoint, it would be a good thing.

Pontius Pilate conveniently washing his hands of the Jesus problem. (Source: Wikipedia Italia)

The story has some wilder elements, such as showing Mary Magdalene as a sort of witch leading a goddess-worshipping cult. Graves ties a lot of mythological features together, drawing interesting parallels from Judaism to Greek, Egyptian, and other mythologies, but sometimes he seems to be stretching it a bit. In his Historical Commentary, Graves writes, “I undertake to my readers that every important element in my story is based on some tradition, however tenuous, and that I have taken more than ordinary pains to verify my historical background.” The result is a thought-provoking look at a familiar story from an unusual angle.

You know you’re in trouble when the introduction to a book warns you that our surveillance society is going to be a nightmare both Orwellian and Kafkaesque. Hyperbole is sure to follow.

You know you’re in trouble when the introduction to a book warns you that our surveillance society is going to be a nightmare both Orwellian and Kafkaesque. Hyperbole is sure to follow. It’s not that Ross Clark doesn’t tackle some unsettling trends. The proliferation of CCTV cameras in the U.K. designed to watch your every move, sometimes even speaking to you when you do something wrong, is disquieting, and certainly invokes scenes from 1984. DNA databases that contain information from the general public have potential for misinterpretation and misuse, and the movement of much of our personal information, including health and financial, to the Internet also has its pitfalls.

The problem is that Clark presents all of these scenarios in the most inflammatory, exaggerated way, making him seem more like a paranoid Luddite than a voice of sanity in an over-watched world. Almost none of his information is sourced in any way, making it hard to check his facts. He loses credibility with me when he moves from talking about the potentials of police misuse of our information, to fearful ranting about the grocery store:

"If there is one nightmare which Orwell failed to foresee it is the voice of the health minister lecturing us for taking one helping of Frosted Flakes too many. . . .there is potentially a darker side. . . .Details of your shopping habits are used. . .to build a picture of you and your neighborhood, so that they can better target you with the type of junk mail to which they think your demographic category will respond" (p. 102-103).

Ross Clark’s Room 101 apparently involves not rats or cockroaches, but junk mail. I don’t like it either, but I think he’s missing the point.

With new technology of this kind, I think we need to ask three questions.

1. What are we trying to accomplish with the technology?

2. Does it accomplish what we want it to do?

3. Assuming it does what we want, is it worth the financial cost, and more importantly, the cost in civil liberties?

If it doesn’t even do what we want, as it appears much of the technology discussed in the book does not, then it certainly isn’t worth sacrificing civil liberty for.

The problem really isn’t the technology itself. Governments have spied on their citizens for centuries. From Caligula to Stalin, the best dictators have been remarkably good at monitoring people’s activity for their own diabolical purposes, with or without cell phone tracking. More concerning than the method of surveillance is how the information is used. In the U.S., the framers of the Constitution made it difficult on purpose for authorities to search your house and your person. They were keenly aware that search and seizure had enormous potential for abuse. The bigger concern in modern society is the gradual chipping-away of the protections afforded by the 4th amendment with laws like the Patriot Act. Orwell’s 1984, despite the pervasive cameras, could not have happened in a setting where those protections were honored, and where a free press kept an eye on things to cry foul when necessary.

*I want to thank the Bird Brian Lending Library for the opportunity to read this book. If anyone wants to read it next, let me know and I’ll send it along. You will have the added bonus of reading the snarky comments in the margins from all of the previous Goodreaders who have read it.

This is a book you really have to finish. Through much of it, I enjoyed it well enough. There are funny moments, though the humor tends to be dark (at times very dark). The depictions of addiction, depression, obsessive-compulsions, phobias, and hyper-competitiveness are insightful and at times have a searing, painful realism. But I felt a lot of the time that in a way it was aimed at a slightly different demographic from me. I could think of a lot of people I’ve known who would be all over this (though I don’t know anyone in real life who has read it). A definable demographic: U.S. males, middle to upper middle class, intelligent, educated, nerdy, probably born sometime between 1965-1985. Don’t get me wrong, I know and love that demographic. As a reader, though, I initially felt like this book was aiming near me, but not quite at me. More important than which group Infinite Jest targeted was the fact that targeting any group at all made it smaller and less universal. A Good book, but not a Great book. Four stars, not five stars.

This is a book you really have to finish. Through much of it, I enjoyed it well enough. There are funny moments, though the humor tends to be dark (at times very dark). The depictions of addiction, depression, obsessive-compulsions, phobias, and hyper-competitiveness are insightful and at times have a searing, painful realism. But I felt a lot of the time that in a way it was aimed at a slightly different demographic from me. I could think of a lot of people I’ve known who would be all over this (though I don’t know anyone in real life who has read it). A definable demographic: U.S. males, middle to upper middle class, intelligent, educated, nerdy, probably born sometime between 1965-1985. Don’t get me wrong, I know and love that demographic. As a reader, though, I initially felt like this book was aiming near me, but not quite at me. More important than which group Infinite Jest targeted was the fact that targeting any group at all made it smaller and less universal. A Good book, but not a Great book. Four stars, not five stars. This is a novel with many flashes of brilliance as well as sustained passages of great writing, but there are also ugly moments. Some were necessary to the story, but at other times I felt like DFW was exorcising his own repellent, obsessive thoughts (the family dying one by one by cyanide poisoning, the details of Lenz killing cats and dogs) by inflicting them onto me. Darkly humorous or not, the more he did it, the less I appreciated it. There were gratuitous cheap horror show tricks and gags that dragged out longer than necessary.

But somewhere around 600 pages or so, I was finally sucked in. Wallace gradually gathers the threads of his myriad story lines together, letting the reader experience epiphany after epiphany as the pieces of the puzzle start to slide into place. It’s a fun feeling when we are finally allowed to step back from a large canvas that we’ve been looking at too closely, to see that the beautifully detailed scenes he has created eventually make sense as parts of a whole.

Then the story starts to get stranger, but proportionally more intriguing. Gately, lying in his hospital bed, dreams/hallucinates/is haunted by memories that only Hal or J.O. Incandenza, people he has never met, could know. Even stranger, the painfully sober Hal thinks Gately’s thoughts (“he hunches, she hunches”), and then Gately thinks in ALL CAPS words that the O.E.D.-obsessed Hal would know (“LISLE,” “EMBRASURE”), but Gately wouldn’t. It’s wild, initially subtle but gradually more obvious, and leaves plenty of questions. Incredibly, at the end of more than 1,000 pages, the natural instinct is to turn back to the beginning to try to figure it all out, in a recursive loop of a story it’s hard to turn away from. That says a lot for a writer who has challenged his readers with frustration, ugliness, and mirrored roadblocks.

Comments on the ending (I am spoiler-tagging this):

I read a quote from an interview with DFW on the ending: "There is an ending as far as I'm concerned. Certain kinds of parallel lines are supposed to start converging in such a way that an 'end' can be projected by the reader somewhere beyond the right frame. If no such convergence or projection occurred to you, then the book's failed for you." I get this, and, while I want to go back and read certain sections again, I do think the clues are all there to let us know what happened. But somehow I still wish DFW were the one telling it, because I know it would be a great story. I see where he is refusing to allow us the passive entertainment of the blockbuster finish, but I still wish we had it. And yet, I think the book is better for his not giving it to us. If that makes any sense.

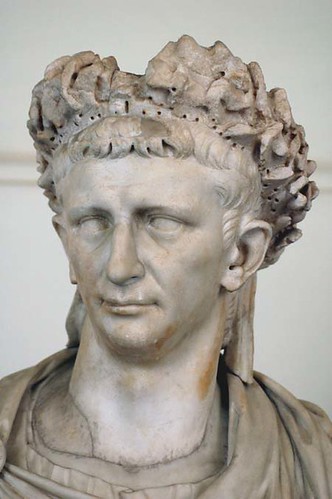

Poor Clau-Clau-Claudius. He stuttered, had a limp, and was deaf in one ear. Considered the family idiot, he had the misfortune to be born into a family that suffered from a congenital lack of compassion.

Poor Clau-Clau-Claudius. He stuttered, had a limp, and was deaf in one ear. Considered the family idiot, he had the misfortune to be born into a family that suffered from a congenital lack of compassion. Robert Graves’s choice of the hapless Claudius as the narrator for this work of historical fiction was ingenious. Seen as dull-witted and harmless by his ruthless relatives, Claudius managed to avoid almost the poisoning, banishment, starvation, stabbing, and suicide to which many of his more prominent associates fell victim. He was the family outcast, but innocuous enough to be left alone to observe the antics of those around him, and, as a historian, he recorded it all to share with us.

Claudius, Emperor of Rome from 41 to 54 AD

Graves does an excellent job of taking us into Claudius’s mind, despite the 2,000 year gap in time. Claudius would have considered himself a “good Claudian” (compared to most of his relatives), but he had his flaws, including a cold indifference to slaves and conquered nations and a fondness for drink and gambling. Still, compared to his nephew Caligula, who made his horse a Senator and had entire sections of the crowd thrown to the lions out of boredom, Claudius can not help but seem refreshingly sane and humane.

Claudius’s grandmother, Livia, is depicted as a devious schemer and poisoner, but Claudius even managed to be fair to her. Though he disliked her as much as she disliked him and had the good sense to be afraid of her, he tells us, “...however criminal the means used by Livia to win the direction of affairs for herself...she was an exceptionally able and just ruler” (p. 228).

Livia, the real power behind Caesar Augustus

Graves occasionally allows himself to give commentary through Claudius. I, Claudius was published in 1934, on the eve of World War II, and Graves doesn’t miss the opportunity to stick it to the Germans. He has Claudius’s brother, Germanicus, say, “The Germans...are the most insolent and boastful nation in the world when things go well with them, but once they are defeated they are the most cowardly and abject. Never trust a German out of your sight, but never be afraid of him when you have him face to face” (p. 249). He gives a plug to the English, too, when he lists as one of three impossible things the idea of subduing the island of Britain (p. 232).

Historical fiction is always a bit risky; when it’s bad, it can be really bad, particularly when characters from hundreds of years ago talk like they’re on an MTV special. I, Claudius, however, is excellent historical fiction. The characters are believable, depicted with wit and even a touch of modern relevance. There is the added bonus that modern taxation doesn’t seem nearly so onerous when compared to Caligula’s, when he imposed “a tax...on all married men for the privilege of sleeping with their wives” (p. 425). This is the kind of story that lets you imagine what it would have been like to live in a different age, and then to feel very grateful that you don’t.

Nobody does Gothic like [a:Daphne du Maurier|2001717|Daphne du Maurier|http://d.gr-assets.com/authors/1357663068p2/2001717.jpg]. A decrepit inn without guests, wild moors, sinister fogs, smugglers, shipwrecks, a dashing horse thief, an albino vicar, and a murder mystery - all of the ingredients are there when orphaned Mary Yellan arrives at Jamaica Inn to live with her aunt who is married to a threatening man with secrets to hide.

Nobody does Gothic like [a:Daphne du Maurier|2001717|Daphne du Maurier|http://d.gr-assets.com/authors/1357663068p2/2001717.jpg]. A decrepit inn without guests, wild moors, sinister fogs, smugglers, shipwrecks, a dashing horse thief, an albino vicar, and a murder mystery - all of the ingredients are there when orphaned Mary Yellan arrives at Jamaica Inn to live with her aunt who is married to a threatening man with secrets to hide.

The plot may seem over-the-top, but du Maurier excels in this genre, carefully laying the groundwork for a creepy, foreboding atmosphere. Instead of giving us a stereotypical plucky, tough-as-the-guys heroine who would be hard to believe in this early 19th century setting, du Maurier creates a more nuanced character, one who “knew the humility of being born a woman, when the breaking down of strength and spirit was taken as natural and unquestioned,” and yet faces her challenges with an understated, steely resolve. Du Maurier was sensitive to the restrictions women faced when she wrote this novel in 1936, and she subtly weaves those concerns into this book.

While not quite at the level of [b:Rebecca|12873|Rebecca|Daphne du Maurier|http://d.gr-assets.com/books/1327871977s/12873.jpg|46663] and [b:My Cousin Rachel|50239|My Cousin Rachel|Daphne du Maurier|http://d.gr-assets.com/books/1170367871s/50239.jpg|623258], [b:Jamaica Inn|50244|Jamaica Inn|Daphne du Maurier|http://d.gr-assets.com/books/1328953668s/50244.jpg|430524] is an enjoyable novel that will be appreciated by fans of du Maurier and Gothic fiction.

Alfred Hitchcock's 1939 film was based on du Maurier's book.

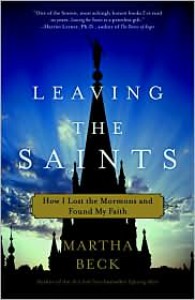

In Leaving the Saints: How I Lost the Mormons and Found My Faith, Martha Beck recounts her experiences in the Mormon church. As the daughter of a highly respected Mormon apologist, the Mormon faith played a foundational role in Beck’s life. She left Utah to study at Harvard, then moved back to teach part time at Brigham Young University while completing her doctoral dissertation in sociology. She returned in part because she found the Mormon community to be more accepting of her young son with Down Syndrome than her friends and colleagues in Boston.

In Leaving the Saints: How I Lost the Mormons and Found My Faith, Martha Beck recounts her experiences in the Mormon church. As the daughter of a highly respected Mormon apologist, the Mormon faith played a foundational role in Beck’s life. She left Utah to study at Harvard, then moved back to teach part time at Brigham Young University while completing her doctoral dissertation in sociology. She returned in part because she found the Mormon community to be more accepting of her young son with Down Syndrome than her friends and colleagues in Boston. The Mormon community’s acceptance of her child’s disability was admirable, but most of the other things she described about Mormonism, from her wedding ceremony with threats of death if she betrayed its secrets, to the polygamy which is still part of church teaching (while Mormons are no longer supposed to have multiple wives on Earth, they can have them in Heaven), to the extremely patriarchal class structure, were disturbing in varying degrees. Beck’s description of the academic limitations placed on BYU professors reads like something out of 1984. While researching Sonia Johnson, a feminist Mormon who challenged the church’s teachings, she found that all references to the woman had been systematically removed from the BYU library. When she looked up citations in newspapers, the sections were missing. If faculty members challenged church teachings, they could be fired and excommunicated. As they had been instructed to publish only in official Mormon publications, regardless of their academic area, it could be nearly impossible for them to find positions in other academic institutions after leaving BYU.

The parts of this book dealing with Mormon history and doctrine were fascinating. Beck was less convincing, however, when discussing her struggle recovering a repressed memory of being sexually abused by her father as a child. Not surprisingly, this revelation creates a major divide in her family as well as within the church, which seems to treat survivors of childhood sexual abuse in a dismissive fashion.

Beck does not come across as the most reliable of narrators. Her eagerness to embrace certain types of phenomena like near-death experiences and astral projection does not seem consistent with her stated insistence on empirical proof. She talks about having a dream that someone named Dana will come to her aid, and then speaks of meeting Diane and Miranda two days later, with several of the same letters as the name Dana, as if that is fulfillment of a psychic prediction. This type of thinking makes her come across as a bit flaky. Beck’s (now ex-) husband left a one-star review of this book on Amazon, challenging her statements that they received phone calls and letters threatening violence and death when he left the Mormon church. Notably, however, her ex-husband does not challenge her statements about what happened at BYU.

Leaving the Saints is a well-written account of several controversial subjects. Beck’s allegations paint a disturbing picture of the hierarchy of the Mormon church, but the book suffers from questions about her credibility.

Dystopian stories are disturbing in proportion to their plausibility. At first, The Hunger Games doesn’t seem particularly feasible, with an elaborate annual event that requires each of twelve districts in Panem (formerly North America) to offer up a boy and a girl as tributes for a match to the death in which only one will survive. The explanation given for this brutal practice is that it is the Capitol’s (not Capital’s) way of punishing and terrorizing the districts for rebelling seventy-four years ago.

Dystopian stories are disturbing in proportion to their plausibility. At first, The Hunger Games doesn’t seem particularly feasible, with an elaborate annual event that requires each of twelve districts in Panem (formerly North America) to offer up a boy and a girl as tributes for a match to the death in which only one will survive. The explanation given for this brutal practice is that it is the Capitol’s (not Capital’s) way of punishing and terrorizing the districts for rebelling seventy-four years ago. Far-fetched as that may seem, the idea of child sacrifice to propitiate angry gods is hardly a new one, and, horrifyingly, still occurs. And of course the ancient Romans enjoyed watching gladiatorial combat for entertainment, a reference Suzanne Collins drives home by giving many of the Capitol’s citizens Roman names.

The modern twist here, though, is that the Hunger Games are a national reality TV event for the citizens of Panem. The subjects in the oppressed districts are forced to watch. The lucky citizens in the Capital, exempt from offering their children in sacrifice, enjoy the entertainment, and the bloodier the better. The Hunger Games are sort of Survivor meets Amazing Race meets Big Brother.

Speaking of Big Brother, I couldn’t help but be reminded of the first season of the American version of the reality television show. During that season, the contestants were mostly fairly likeable, unwilling to engage in cutthroat antics like their more scheming counterparts on Survivor. America didn’t help much by repeatedly voting out anyone controversial or ambitious. By the end of the season, viewers were treated to scintillating scenes of the cast amiably putting together a jigsaw puzzle together. While that might speak well for humanity, it was a disaster for ratings. When the show miraculously came back for a second season, it had been completely revamped, with a far more competitive cast and nastier scenarios. Soon contestants were secretly cleaning toilets with each other’s toothbrushes, and ratings soared. The show is now in its 14th season.

Would people really want to watch something as horrible as the Hunger Games? It seems ludicrous, yet round-the-clock Misery Channel coverage of events like Princess Diana’s death and the OJ Simpson trial seemed to initiate an era where we lap up disasters with an almost gleeful enthusiasm. Reality TV followed, with the nastiest, most scheming contestants bringing in the highest ratings. Perhaps it’s best not to think too hard about how such entertainment would be received.

A Kind of Compulsion is Volume 10 of The Complete Works of George Orwell. The first nine volumes are Orwell’s books. Volumes 10-20 contain his letters, essays, poems, journalism, book reviews, movie reviews, diaries, drawings, tax records, long division calculations, grocery lists, ticket stubs, and sudoku puzzles. Okay, I’m exaggerating a little bit, but only a little (I’m not kidding about the long division).

A Kind of Compulsion is Volume 10 of The Complete Works of George Orwell. The first nine volumes are Orwell’s books. Volumes 10-20 contain his letters, essays, poems, journalism, book reviews, movie reviews, diaries, drawings, tax records, long division calculations, grocery lists, ticket stubs, and sudoku puzzles. Okay, I’m exaggerating a little bit, but only a little (I’m not kidding about the long division). This volume is aptly titled, because editor Peter Davison clearly had a kind of compulsion in trying to track down everything Orwell wrote. Ever. He then meticulously traced and verified it all, working out dates for undated material, identifying all of the people referenced in letters, analyzing Orwell’s writing in the Eton school paper to see if unsigned pieces were written by him, evaluating anything anyone who knew him had written or said about Orwell to help place material, and footnoting everything with all of this information. Davison faithfully notes where Orwell has crossed things out and misspelled words (Orwell apparently had trouble with the words “aggressive” and “address” his entire life). You can get a visual sense of the type of effort involved here by looking at Davison’s editing of Nineteen Eighty-Four: The Facsimile of the Extant Manuscript (my review has some pictures), where he valiantly deciphered handwriting and typescript. Extrapolate that to the thousands of pages involved in The Complete Works to get a sense of what a monumental task this was.

Volume 10 covers the years from 1903-1936, giving the widest variety of writing in The Complete Works. The first item is a 1911 letter from eight-year old Eric Blair in boarding school, writing home to his mother:

Dear Mother

I hope you are quite well, thanks for that letter you sent me I havent read it yet. I supose you want to know what schools like, its ? alright we have fun in the morning. When we are in bed.

from

E. Blair

There are articles from the Eton paper, short stories, newspaper pieces in French with corresponding English translations, and a play about Charles II that Orwell wrote for his students to perform when he was a teacher, with large sections in blank verse. Later letters involve the publication of his earlier novels and the changes he had to make to avoid libel charges (a very serious issue at the time that could involve jail sentences for writers, publishers, and even the printers), as well as his research for The Road to Wigan Pier.

I’ll conclude here with one of Orwell’s sketches for Burmese Days (handwritten in ink on reverse of Government of Burma paper), an epitaph for John Flory. I think it’s kind of catchy.

JOHN FLORY

Born 1890

Died of Drink 1927.

Here lies the bones of poor John Flory;

His story was the old, old story.

Money, women, cards & gin

Were the four things that did him in.

He has spent sweat enough to swim in

Making love to married stupid women;

He has known misery past thinking

In the dismal art of drinking.

O stranger, as you voyage here

And read this welcome, shed no tear;

But take the single gift I give,

And learn from me how not to live.